Saturday. This morning arrived here Fr Charles Houben from Highgate, London, being appointed for this community. Fr Charles is well known in this city of Dublin as well as throughout Ireland for the many miraculous cures people say [they] have received by his blessing them with the relic of St Paul [of the Cross], and by using Holy Water blessed with the same relic. Fr Charles was one of the first Fathers who came to Dublin after its foundation in 1856 and had left in 1867, when he was removed from Dublin for the reason of his having become too remarkable for extraordinary cures.

This entry in the diary of Fr Salvian records for us the return of Charles of Mount Argus to 10 January 1874. The news of his arrival spread quickly and, within a short time, the daily pilgrimages of sick and suffering had begun once more. The people of Ireland had not forgotten him during his eight years of exile; they remembered Charles as someone who always had time to listen to their troubles, one who was always ready to comfort those in need and show them the goodness and loving kindness of God our Saviour.

In the Ordinary and Apostolic Processes, the two most striking aspects of Charles’ life, referred to again and again, both in the evidence of his fellow-Passionists and in that of people who had sought his help, are that he was always available to those in any kind of suffering, and that he lived continually in the presence of God.

In its Document on the Ministry and Life of Priests, Presbyterorum Ordinis, the Second Vatican Council affirmed that priests ‘cannot be ministers of Christ unless they are witnesses and dispensers of a life other than this earthly one. But,’ the document goes on to say, ‘they cannot be of service to people if they remain strangers to the life and conditions of men and women’ (par. 3). Charles is a clear example of someone who witnessed to spiritual values by a life of prayer and, at the same time, was completely involved in the day-to-day reality of the lives of the men and women of his time.

In a letter to his brothers and sisters, written from Mount Argus, Charles says, ‘My duties in the monastery are as follows: I say Mass every day; I preach and hear confessions; I say prayers and bless the people who come to the church.’ As always, he says nothing about the cures which were taking place. For information about these we must turn to others. A Dublin businessman, John Patterson, tells his story:

In a letter to his brothers and sisters, written from Mount Argus, Charles says, ‘My duties in the monastery are as follows: I say Mass every day; I preach and hear confessions; I say prayers and bless the people who come to the church.’ As always, he says nothing about the cures which were taking place. For information about these we must turn to others. A Dublin businessman, John Patterson, tells his story:

I saw Fr Charles when I was about six or seven years of age. That was in the year 1876. I was stone-blind as the result of an accident which occurred when I was nearly four-and-a-half. I was hammering a rock of some kind and a lot of chips flew off and struck both eyes. I had perfect vision before this and was at school. I was at least eighteen months blind. I was brought to two or three oculists who treated my eyes, perhaps by drops. At any rate, I know that the treatment was painful. I do not know what was the supervening cause of the blindness; and there is no person now living who could give information on this point. I suppose I could have distinguished day from night during these eighteen months, but I could not see anything. My step-mother and father often refer to the fact that I was blind during this period. Members of the family and strangers were also convinced on this point. Some lady whom I don’t know told my step-mother who was a Protestant to have me brought to Fr Charles. This lady brought me to Mount Argus. I came in a cab, and was led into the church. I could see nobody, and I thought I was alone in the church. I was brought to the altar-rails. All I remember clearly is that in a moment I saw Fr Charles with his hands extended horizontally towards my eyes. I did not hear him speaking, and I do not know whether he touched my eyes or raised my eyelids or not. I then left the church but I don’t remember having seen anything on the way out. When I was leaving the grounds of Mount Argus, I looked to might right hand side and saw a cow. I cried out, ‘Oh! Look at the cow.’ The cow appeared to me to be very small: and the field seemed to be in a hollow, whereas it was really level. The lady who accompanied me was surprised and said that it was a cow. I am sure it was the same evening that I saw all the members of the family. I remember that there was excitement in the house at my return.

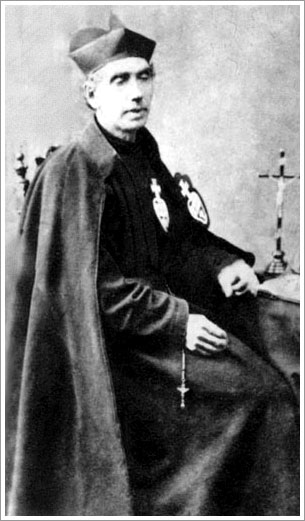

Once again Charles’ ministry was not confined to those who came to see him at Mount Argus; day and night, he was ready to visit the sick in their homes or in hospitals. above: Father Charles, c. 1875

On the occasion of Fr Charles’ visit to the house of which I will speak, a great crowd had assembled in anticipation of his coming, and even a Protestant woman asked him him to come and bless her child, which he did.

I believe Fr Charles worked a miracle in the case of my uncle. It was in the year 1878, or thereabouts, when my uncle was thirty-two, and I about fourteen. I lived in the same room with this man. I have a perfectly clear memory of what happened. Once morning my uncle did not come to work as usual, and word was brought that he was spitting blood. I never heard that he spat blood previously. The doctor -- a famous Dr Hamilton -- came to see him and said that he could not live beyond that night. The doctor applied no remedies, contenting himself with advising my uncle to set his affairs in order and send for the priest. I don’t remember having heard the doctor say where the haemorrhage was. The haemorrhage was very copious. He vomited more blood that one would think that the body could contain. My uncle’s wife suggested that Fr Charles should be sent for. The sick man ad received the last sacraments. He was very weak and could not stir when Fr Charles came in the afternoon. He was conscious. I was in the house at the time, but was not present at the interview between Fr Charles and the sick man. Fr Charles came into the room in which we were assembled awaiting results and said that the man would be all right. This put our minds at ease as we had great trust in Fr Charles. Fr Charles said he would visit him again, and so he did, after about two days. Immediately after Fr Charles’ first visit the haemorrhage stopped and was better in every way. My uncle remained in bed until after Fr Charles’ second visit. After Fr Charles’ second visit he got up and went out, and carried on his business as well as ever. The doctor came again shortly after Fr Charles’ visit and expressed astonishment to the Keogh family that the man was alive and well. The doctor had no further trouble with him. He never got a haemorrhage again, and died as the result of contracting a cold in 1885.

The ‘great crowd assembled in anticipation of his coming’, described above by John Hendrick, is reminiscent of a scene from the Gospel or the Acts of the Apostles. So great was people’s confidence in his prayers and his blessing that large numbers would gather outside any house he visited and, even as he went along the street, sick people would be brought out of their homes to be blessed by him.

When I was a very small baby, about three or four months old, my uncle let me fall. I developed spinal disease. I was bent double, my head bent back and my hands resting on my knees when I tied to walk, on crutched till nine years. One day (we lived then in Mercer Street) my mother happened to bring me out of the house when Fr Charles was passing. He asked who I was and what was wrong. My mother told him and he blessed me and told me to say one Our Father and three Hail Marys each morning and night in honour of the Passion. In about two or three months I could walk straight, my head in normal position, and my hands and arms also normal. During the two months the improvement was gradual and I have remained in good health ever since.

In spite of the constant demands being made on his time, Charles never gave the impression of being someone who was caught up in a whirlwind of activity, On the contrary, even while engaged in his ministry he seemed to be totally absorbed in God:

I knew Fr Charles personally from about 1869 when I was a schoolboy. I often saw him and spoke to him from that until he died.... I am sure Fr Charles was a man of uncommon holiness. I recollect especially his attitude which clearly showed that he was absorbed in prayer and oblivious of his worldly surroundings: he always had a prayer book or crucifix in his hand. I remember well the wonderful smile which radiated from his countenance when I saw him speaking words of comfort to a poor boy who was suffering: he seemed transformed and even handsome, though normally he was by no means good-looking.

Elizabeth Costello, who testified at the Apostolic Processes, was the daughter of John Smyth, a Dublin cab-driver, who often was sent to Mount Argus to bring Charles to the sick and the dying:

My father was a cab proprietor and very frequently drove Fr Charles on his visits to the sick. In this ministry Fr Charles was most devoted and responded most readily to all calls....

When being driven about to the sick, he would be entirely absorbed in prayer and quite unconscious of his surroundings. He would have to be called when arrived at his destination. My father told me that Fr Charles was always praying. When going to the sick in his cab, Fr Charles prayed all the time: if it was dark, he had to be given a candle to read by. On arrival at the end of his journey, he would be so absorbed in prayer that he would have to be called,

Sometimes my father had to accompany him twice in the same day on his rounds or visits. These visits were made in all weathers and at all times, often late at night. Fr Charles seemed to respond immediately to any call upon his charitable ministry.

Before blessing a sick person he would usually pray spontaneously for some time; often too he would write out prayers for those who came to see him, prayers which were always simple and adapted to those who would use them. Here is one, given to a little girl in June 1877 for her First Communion:

Sweetest Mother of God, lend me your heart to place the little infant Jesus on it. Praise, adore and love Him for me, as you can do it so much better than I. Amen.

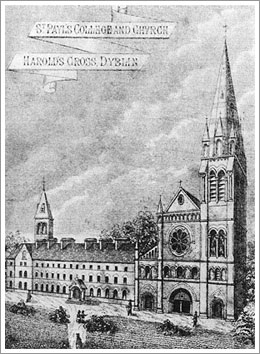

When St Paul’s Retreat had been opened in 1863 the community had been unable to proceed with the building of the church. The original drawing on the monastery-to-be, by McCarthy, had included at the east end of the building a church with an enormous spire, more neo-gothic than romanesque in inspiration. Fortunately, when in the 1879s work began on the new church, the plans for this building could not be found. McCarthy now came up with a better idea: a romanesque facade with twin towers, which would blend much better with the monastery and give us Mount Argus as we know it today. above: original drawing for the church at Mount Argus

When St Paul’s Retreat had been opened in 1863 the community had been unable to proceed with the building of the church. The original drawing on the monastery-to-be, by McCarthy, had included at the east end of the building a church with an enormous spire, more neo-gothic than romanesque in inspiration. Fortunately, when in the 1879s work began on the new church, the plans for this building could not be found. McCarthy now came up with a better idea: a romanesque facade with twin towers, which would blend much better with the monastery and give us Mount Argus as we know it today. above: original drawing for the church at Mount Argus

James Burke was in his early twenties when work began on the church:

I knew Fr Charles from the year when the new church was started here, about sixty years ago. He was the talk of the whole district.... I came here to work on the new church and shortly afterwards he called me aside and said to me, ‘There was an accident here already to one of the workmen: tell the others not to be afraid; there will be no other accident.’

He was always praying: you could see his lips moving in prayer. He went round the new church building everyday for about six months in the early stages of the work. We believed that he was praying that there might be no further accident. He walked slowly, with eyes down-cast, looking at nobody and speaking to nobody. I was the only one he spoke to. The workmen had great respect for him and had great faith in his promise that there would be no more accidents.

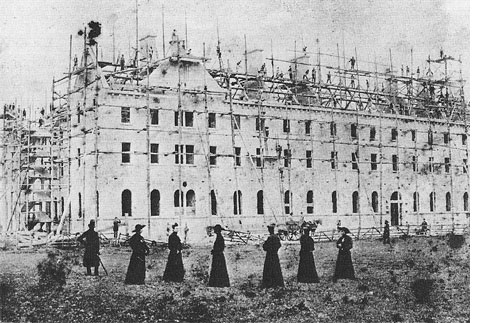

above: builders at Mount Argus

It almost seems as if building was only possible at Mount Argus when Charles was in residence. The foundation stone of the church had been laid with great solemnity on 28 June 1866, just four days before Charles had been transferred to England, but it had remained alone and surrounded by weeks for eight years, waiting for him to return. Now that he was back at Mount Argus, supporting the work by his prayerful presence, the new church began to take shape.

On 28 April 1878 (at that time the feast of Saint Paul of the Cross), Dr McCabe, later Archbishop of Dublin, blessed the new St Paul’s Church, Mount Argus, A Dublin newspaper carried this description of McCarthy’s masterpiece:

It is a superb specimen of the majestic romanesque style. The great western front flanked by campanile towers in pierced by three ample entrances, formed beneath an arch and moulded portico, above which are semicircular lunettes containing groups in high relief, representing scenes in the life of St Paul of the Cross; that on the left hand being St Paul while an infant, rescued by the Blessed Virgin from being drowned; in the centre the Blessed Virgin showing the habit and badge of the Congregation of the Passionists to St Paul; and at the right Pope Benedict XIV, approving of the Rule of the Congregation.

One of his contemporaries, a fellow-Passionist, tells us that ‘God alone is cognisant of all that Fr Charles did to make Mount Argus what it is. He alone knows the number and the value of his deeds which are so precious in Heaven’s sight. The period from 1857 to 1893 (with the exception of a few years he spent in England) were passed by him within its walls, and his name will ever be entwined with its history.’ We can say of Charles, as was said of the man who built another St Paul’s, ‘If you seek his monument, look around you.’

top of page

© Paul Francis Spencer, C.P. 2007 - 2020 - all rights reserved

This biography, paper-published in 1988 at the time of Father Charles’ beatification, was how I became acquainted with the life of Father Charles. Although you will find the entire text at this site, I encourage you to look for the new paper edition of the book, which will be available in bookshops in mid-2007.